Cognitive Error and Bias

There are numerous reasons that our systems of thinking can be distorted leading to mistakes in judgement. Fortunately the systems we work within clinically attempt to reduce the effect and potential harm most of the time, however, the same systems can sometimes exacerbate these biases.

Where possible I will also talk about ways of mitigating the consequences of these biases. Most of the time just having awareness and remaining cognisant will go a long way to doing this.

Anchoring Bias

When working with undifferentiated patients anchoring is one of the most important biases to be aware of. When we looked at Bayesian thinking and conditional probabilities we spoke about how we adjust our opinion as new information presents itself. An anchoring bias is almost the complete opposite, its putting too much weight on a piece of information. That is disproportionately attributing high probability to that piece of information when reaching a conclusion. It is often the first piece of information acquired.

When looking at medical error and mistakes one of the commonest sources of problems is when cases are handed over between clinicians. Now there are obvious potential issues with a new clinician taking over the care of an individual patient or a group of patients, but in new presentations ie those in an assessment area or an emergency department, relying on the opinion of the clinician before you (anchoring) is one that isn’t always considered. We tend to trust people and particularly colleagues and so leave ourselves exposed to inheriting their misjudgement, even when presented with new information that is contrary to the working diagnosis.

Clearly this isn’t just a problem with handovers, it also works in history taking. Clinicians will often ascribe an initial impression early in their assessment of a patient (Type 1 thinking) and are at risk of ignoring other pertinent pieces of information that don’t fit into their current mental model of the patient’s illness.

Hopefully just in describing clinical examples of anchoring (and there are plenty more) you can start to see and understand what we can do to mitigate the effects of it. Note it would be naive to think ourselves to being immune to any form of bias – they are part of our brain functioning as much as breathing faster and deeper is when we exert ourselves.

Best forms of mitigation are through the structures of the systems around us and in the habits in which we approach clinical thinking and interactions. For example, protocolising investigations and treatment plans reduced the burden on the individual and so reduced the effect any bias may have. The counter factual to protocolised care is that it may introduce an anchoring bias eg they have had an ECG so this is a cardiac problem (admittedly this is an over simplification but you get the point). When junior clinicians start working with undifferentiated patients a lot of the training they receive focuses on forcing them to form a board differential and then talk about how they can logically exclude some and to challenge how they have weighted each in turn. This is a very useful exercise, in this context because it gets them to confront their anchoring biases, but it also exposes their unknown unknown and known unknowns and provides opportunity for teaching.

Interestingly there is some research in medical professionals suggesting happier clinicians are less susceptible to anchoring bias. There is also a correlation between individuals prone to anchoring and how they express in the Big 5 Personality traits (openness, neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness). Those high in agreeableness, conscientiousness and neuroticism are more likely to be affected by anchoring.

Apophenia

This is the tendency to see meaningful connections between unrelated things. Whilst it was initially used to describe delusional thought patterns in schizophrenia it has since been used to describe the human propensity to seek pattern in random information – the “next one must land heads”. It is also a common feature of conspiracy theories.

In medical practice it bares significant importance. In the context of the undifferentiated patient with a new presentation and our aging population meaning they have an increasing number of symptoms and complexity, it is easy to see how we could get 2+2 to equal 5. Now hopefully it is easy to see that there is less significance to an individual patient if we start over investigating because we are wondering if the COPD patient’s shortness of breath could be related to a new PE or not. But on a systems level this is potentially disastrous – resource use and harm from investigations being the main issues.

The counter concept to Apophenia is Occam’s Razor. That is if you have two competing ideas to explain something, the simplest explanation is the most likely. To me, this seems almost like the second law of thermodynamics but in ideas. That is the idea that is the most stable is the one with the lowest energy level (admittedly this might be stretching the analogy a little).

Availability Heuristic

Availability Heuristic/Bias is the consequence of humans weighting a recent or significant event/piece of information more greatly than it truly deserves in the decision making process. Our processing attributes more weight to information that is easily available – the easier it is to recall the more important it must be.

This is the full explanation of recency bias, something I was much more familiar with. It makes sense from an evolutionary point of view that significant and recent events are held with more weight – avoid going near the lion’s den again, or there are berries over there. Availability Heuristic is a step further than recency bias, as it includes significant events that remain easy to recall.

All those who work in health care will have cases/patients/situations that live with them. Usually they are negative experiences as these have a greater imprinting effect on our memories. These experiences will continue to change how we practice and make decisions going forward, they have bigger impact the more recent the event was – a recent missed diagnosis makes every patient have that potential diagnosis, a rare complication leads us to do everything to prevent it from happening again etc.

Often these experiences can make us better clinicians in the long run but, we have to be careful that we aren’t putting other patient’s at risk due to our recent experiences – the prevalence of a PE doesn’t go up just because you’ve recently missed one.

Interesting spin-offs that would come under the umbrella term of availability heuristics would include Salience Bias (prominent or emotive features gain more focus than those that are unremarkable, even if this isn’t true objectively), Selection Bias and Survivorship Bias.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive Dissonance is the mental discomfort people feel when their believes and actions are inconsistent and contradictory. Whilst like it might seem that this has little impact on those trying to practice medicine, there are types of cognitive dissonance that are relevant:

- Normalcy Bias, the refusal to plan for or react to a disaster. (think initial responses to COVID-19, but also our desire to want things to be alright for our patients.)

- Effort Justification, the value of the outcome is greater the more effort put in.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy, the desire to keep going with something due to prior effort regardless of whether it remains a good idea or not. This is also an anchoring bias. (Clinical Scenario that jumps to mind is the desire to keep treating people who have already had a lot of input, think about a deteriorating patient that has had a lot of cancer treatment or the surgical team who want to do just one more operation)

Confirmation Bias

Now this is a biggy. Confirmation Bias is the tendency to search for, focus on and remember information that confirms one’s preconceptions. It a clinical context, this would be relying too much on one’s clinical gestalt, or minimising parts of the history that doesn’t fit with your type 1 thinking, ie the impression you initially formed.

Congruence Bias is a type of confirmation bias and is particularly relevant to working with undifferentiated patients and requesting testing. It is the tendency to test hypotheses exclusively through direct testing, instead of testing possible alterative hypotheses. The example that jumps to mind is in chest pain presentations only doing a trop because we think it might be an MI whilst ignoring the fact that it could also be a PE, pneumothorax, dissection etc etc. As you can probably see, especially if you have looked at our pretest probability section, there is a trap whatever you do – under investigate and you are at risk of Congruence Bias, over investigate then you risk exposing your patient to unnecessary testing and potential incidental, irrelevant findings that should have no effect on your final views (Saliance Bias and Apophenia).

Egocentric Bias

This is an umbrella term to cover a whole load of biases that rely too heavily on one’s own perspective or when your perspective of yourself if different from others. I have included the ones that are more relevant in a healthcare setting as the list is long, just because I haven’t included a specific bias doesn’t mean its not important or relevant, I just think others are more so.

- Bias Blind Spot, tendency to see oneself as less bias than others.

- False Consensus effect, this is a particular risk when uncertain clinicians are falsely reassured during a group handover and no one challenges the mistakes they have made. For senior clinicians leading the hand over this creates a dilemma – do you call out mistakes or misjudgements in front of the group to prevent this kind of bias and maintain standards, but this comes at the cost of potential humiliation and creating Availability Heuristics in others.

- False Uniqueness Bias as relevance to clinicians wellbeing more than to their care of patients. This is the tendency to see projects and themselves as more singular than they are, often aligning themselves more with how they wish to be seen rather than the reality. It is the opposite of false consensus. I suspect this plays some role in the individual responsibility that clinicians can feel for systemic error and issues that complicate their day to day work lives.

Framing Effect

This is the tendency to draw different conclusions from the same information, depending on how that information is presented. When presented with positively framed options people are more likely to make risk avoidant options, whilst the converse is also true.

Whilst the fundamental psychology is about risk aversion given positive or negative spins, there is relevance to healthcare. This effect can underpin all our perspectives - are we in an area that treats sicker patients? Then we are more likely to be risk adverse. Does the patient present their view positively? Then we are more likely to be risk tolerant. I am sure you can think of many other examples.

Some thought experiments to fit along these lines – how willing do you think people are to discharge a patient home from a resus environment? Would an anaesthetist (who has a different perspective of risk in an ED) be more or less willing to sedate a patient than a ED clinician in resus? Does the ED clinician’s tolerance to accept good enough reflect that they don’t have to deal with negative consequences as much? For example the manipulated fracture that is almost perfect, the surgeon is more likely to have to see the patient again and potentially operate, but the ED clinician is likely to never see them again. Would a clinician change how they treat a patient on the ward compared to how the would if exactly the same patient was in clinic (would they discharge or admit them?) – some of the thought here is summarised in the project to end pyjama paralysis. Which is essentially confronting framing bias of patients in bed being ill. This effect is on both clinicians and the patients themselves – “I am in bed on a ward therefore I must be unwell” “the patient is still in bed, they aren’t well enough to be at home” vs “I am up and moving and doing better”. Obviously there are also benefits to not being in bed all the time alongside the framing readjustments.

Logical Fallacy

The GI Joe Fallacy is an ironic one for a session on Cognitive Bias, it’s the tendency to think that knowing about cognitive bias is enough to overcome it. The name comes from the TV show that ended with the catchphrase “now you know”

Prospect Theory

Is a noble prize in economics winning concept demonstrating how people are loss averse and are not rational (expected utility theory). It is useful to be aware of to help us understand people but has limited direct clinical correlation as we work to minimise the uncertainty and risk involved. There is less win and lose, more establishing the best course of action

Self-Assessment

Self-assessment bias is a tendency to overestimate ones own professional performance relative to social comparison group – in studies done in psychotherapist, there was a tendency to think they we much better than their colleagues (on average they reported themselves to be at the 80th centile, when obviously the average should be 50th . Interestingly when this study was repeated in the UK, rather than the US, the bias was much less.)

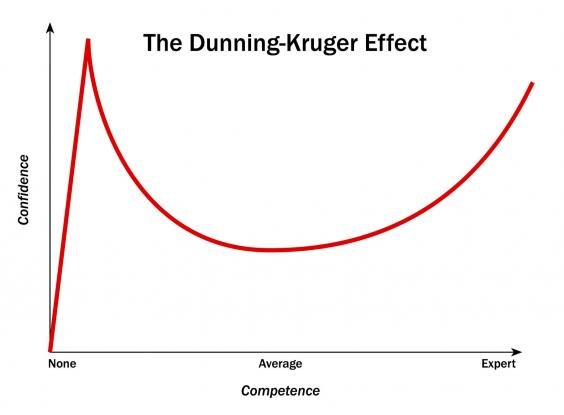

This bias was demonstrated by Dunning (of Dunning-Kruger Curve fame) in healthcare settings and staff confidence but also in people estimating their own health risks when compared to others.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect is a Self-Assessment bias in which people with limited competence in a certain area over estimate their abilities. There is also the mirrored effect where high performing experts underestimate their skills. I suspect in medicine this is a continuation – our confidence and assessment of ourselves fluctuates but rarely to we actually get worse at our jobs. If you look at the graph to the right, I wonder if you could plot it end on end with the effect dampening over time.

Imposter Syndrome is another example of a Self-Assessment Bias, although it is the opposite of the typical assessment – its that fear of being caught a fraud, stemming from the doubt over achievements, skills and talents.

Truth Judgement

These are biases of how our perception of facts can be distorted. Hopefully we are able to overcome these as medical professionals but as we have discussed – no one is immune to any form of cognitive bias, and the believe that we might be is a bias in itself.

Belief Bias – our evaluation of the logical strength of an argument or statement is effected by whether the conclusion is aligned with our current beliefs. We judge the argument on the plausibility rather than then logic or justification of the conclusion. We see the effects of this in day to day life, particularly in politics where the population will believe certain statements as they reinforce and agree with their preconceptions of the world, rather than examining the evidence behind them – think about the economic argument around immigration (it has been long proven that immigrants are a net addition to a country’s economy rather than a drain but there are large parts of the media/politics that would have you believe otherwise, despite an absence of evidence).

Illusory Truth Effect – Now there is a risk we end up too political for a website about medicine, but this is the concept that the more times a false statement is repeated the more likely it is to be accepted as true. When people assess truth they rely on whether the information is in line with prior understanding or if it feels familiar. Aside from politics, social media and echo chambers, advertising also takes advantage of this cognitive bias – you are much more likely to reach for the more familiar product, but they can also give you an impression of a product just by bombarding you with that impression.

More amusingly Rhyme as Reason Effect is the concept that rhyming statements ae perceived as more truthful. There are a lot of studies on this type of effect but it seems that this maybe the original.